The Quaker Family in Colonial America: a Portrait of the Society of Friends by J. William Frost

Much equally New England was shaped by its Puritan heritage, the history of Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley intertwined heavily with the Religious Society of Friends. Philadelphia gained ane of its nicknames, "The Quaker Metropolis," from its founding and settlement by the Friends, colloquially known equally Quakers, a historically Christian religious sect that emerged during the English Civil War (1642-51). Although less influential in Philadelphia later on the eighteenth century, the Religious Guild of Friends remained a vital part of the city's religious landscape.

George Fob founded the Quaker faith after traveling England seeking religious truth. The new movement quickly spread beyond the land and into Northward America. (Library of Congress)

Quakerism grew out of the ministry building of George Fox (1624-91), a shoemaker'southward apprentice who rejected the special authority of university-trained priests and ministers, arguing that divine revelation was accessible to anyone. Fox believed that Jesus "had come to teach his people himself" and that this occurred in the grade of an "inward light" that was present and accessible to human being beings. Past gathering together in silence with other believers, which was called a "Coming together for Worship," Quakers believed that individuals might be straight influenced by God to offering vocal ministry building.

I of the notable features of this new religious group was its relative egalitarianism. While early Quakers did not seek to abolish all earthly hierarchies, they spurned established custom by addressing everyone (including those of higher social status) using the breezy evidently oral communication of "thee" and "thou," language that was commonly reserved for intimates. One embodiment of Quaker faith was the adoption of "plain dress," unadorned wearable designed to defy the custom of having fashion signify social status. In pursuit of this same social goal, men in the Quaker sect violated established custom past not doffing their hats to their social superiors.

Until the early twentieth century, the Quaker belief in simplicity dictated that members of the church wearable obviously dress, a practice that increasingly set up them apart from mod order. (Historical Social club of Pennsylvania)

This concept of equality besides extended to the idea that both sexes were equal in spiritual matters. Early Quakers believed that women had the same authorisation to preach in meeting as men did, and, like their male counterparts, women oftentimes traveled in their ministry. Within and amid local congregations (Quakers called these "Meetings"), committees of women known as "Womens' Meetings" were empowered to carry out some of the grouping'south administration, and their decisions were supposed to be of equal value to the governance provided by the "Men's Meetings."

The Quakers' understanding of Christianity led to the group being different from its neighbors in other means. They professed a "peace testimony," which called on their members to avoid violence and warfare. And though it was a mutual requirement in courts of constabulary at the time, Quakers also refused to swear oaths, arguing that Jesus had forbidden the practice in the New Testament. Because of these differences and their belief that they alone correctly skilful Christianity, Quakers were endogamous, marrying only within their own group and expelling members who married non-Quakers.

William Penn's "Holy Experiment"

Because of their distinctive religious practices and their rejection of the established Anglican Church, the Quakers endured meaning persecution in England and thousands were forced to pay fines or imprisoned. By the 1670s Quakers had begun to consider the possibility of immigrating to North America to escape religious oppression. In 1680 William Penn (1644-1718), a prominent leader with the Quaker movement, received a country grant for a new colony from English monarch Charles Two as a payment for a debt that the king had owed to Penn's father, William Penn. The elder William, who had been an admiral in the Royal Navy, became the namesake for the new colony.

Pennsylvania was founded equally a Quaker colony by William Penn. Co-ordinate to legend, he fabricated a treaty with the local Lenape Indians vowing eternal peace between Quaker colonists and natives. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

Penn saw the colony as a religious venture, a "holy experiment," and he designed the laws of the new colony to be fraternal to Quakers. No oaths were required in courts or to hold public offices, Quaker-way wedlock ceremonies were made the legal form of marriage, and because of past Quaker experiences with persecution, religious liberty was extended to all monotheists.

The colony's majuscule, Philadelphia, became the site of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (PYM), an aggregation of Quakers in the Philadelphia region. Extending over a particular geographic location, PYM comprised several Quarterly Meetings, which in turn were equanimous of multiple Monthly Meetings (like to congregations). Though technically separate from the civil authorities, important Quaker men tended to be elected to make full leadership roles in both bodies, and so much so that historian Arthur J. Merkel has suggested that "the relationship [of the Yearly Meeting] with the government resembled an interlocking directorate." Though other Yearly Meetings existed in New England, Maryland, and N Carolina, PYM before long became the most influential grouping outside of London.

War and Peace

By the 1750s Quakers' interest with Pennsylvania politics began to conflict with their commitment to nonviolence. In 1754 when the French and Indian War began, the British authorities instructed Pennsylvania to equip an regular army to prepare to fight. Many Quakers in the colonial legislature were initially willing to comply. Still, later Catherine Payton (1727-94), a visiting English Quaker minister, exhorted them to adhere to Quakerism'due south peace testimony, many reconsidered. When the Assembly voted to become to war regardless, Quakers resigned en masse rather than violate their peace testimony. Every bit historian Rebecca Larson has explained, this was "the beginnings of a move that would finally end with the consummate exodus of Quakers from government xx years afterwards." Over the next several centuries, but a small number of Quakers accept served in elected positions. Many Quakers, however, redirected their public-service energies into various forms of philanthropy, an arena where Quakers have brought high participation and leadership.

The consequence of Quaker participation in war arose once again during the American Revolution. Most Quakers refused to accept part in this disharmonize because of their avowed pacifism, causing persistent accusations that they were loyal to the British crown. Some Friends were disowned, or expelled, from Quaker Meetings for serving with the American army. These included a small group that founded a splinter denomination, the Gratis Quakers, which existed into the early on nineteenth century.

By the early on eighteenth century some Quakers had become increasingly skeptical about the compatibility of slavery with their religious convictions. By the early 1700s, the PYM and other Yearly Meetings began exhorting Quakers non to import enslaved people, and in the ensuing years they put out a number of pronouncements advising Friends to avert slaveholding. Influential Quaker members of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, particularly John Woolman (1720-72) and Anthony Benezet (1713-84), stressed the immorality of slaveholding and its tendency to corrupt masters into such sins as haughtiness, laziness, and violence.

Beginning in the 1690s, individual members' arguments confronting slavery became increasingly song and insistent. By the 1770s, PYM's constituency had become mostly united behind the policy that whatsoever Quaker who bought, sold, or held slaves should be barred from membership. In subsequent years PYM helped to coagulate the national efforts to petition Congress to terminate the slave trade entirely.

Quakers Support an Abolition Club

Philadelphia Quakers' disdain for slavery led them to help plant the nation'due south commencement abolitionist system in 1775, when seven Quakers were among the 10 men who gathered at the Rising Sun Tavern and created the Order for the Relief of Free Negros Unlawfully Held in Bondage. This society brought a number of lawsuits to secure the liberty of African Americans who had been kidnapped into slavery, or whose rights had otherwise been breached. In 1787 (after state legislation in 1780 provided for the gradual abolitionism of slavery in the commonwealth) the group expanded to include more than non-Quakers, and renamed itself the Pennsylvania Abolition Lodge, also expanding its mission to include slaves. The adjacent generation of Pennsylvania Quakers included a number of leading abolitionists such as noted Quaker minister Lucretia Mott (1793-1880); these radicals spearheaded the creation of the Philadelphia Female Antislavery Gild in 1833.

Slavery was not the but social issue about which Philadelphia Quakers were vocal. In the late eighteenth century they were pioneering reformers, creating a number of organizations designed to amend life for their neighbors. Quaker women in detail were active in establishing Philadelphia's first philanthropic and charitable societies. The Female Order for Relief of the Distressed, founded in the 1790s, sought to minister to the "Inner Low-cal" in every individual by wearable, feeding and providing nursing care to the poor, while the Aimwell School was established to provide master education to poor girls.

Prison reform was another fundamental business organisation of Philadelphia Friends. In the 1770s a group of Quakers founded the Philadelphia Lodge for Relieving Distressed Prisoners, which was intended to improve weather condition in the city's prisons. During the ensuing decades this group was heavily involved in developing the Walnut Street Jail, the first "penitentiary" in the United States. At Walnut Street, rather than incessant labor, prisoners were to be allotted placidity time by themselves to reflect, to read the Bible, and to be visited past church members who would help them to "repent" and to bear meliorate in the future. The concept backside the new institution was drawn partially from Quaker religious practices, stressing the value of silence to facilitate an run across with the divine. These concepts, starting time implemented at Walnut Street, became the prototype for the construction of Eastern State Penitentiary and the footing for the widely adopted "Pennsylvania System" of prison house management.

Friends Divided

Quakers split up over theological differences in the 1820s. Controversial preacher Elias Hicks was at the center of the controversy. (Library of Congress)

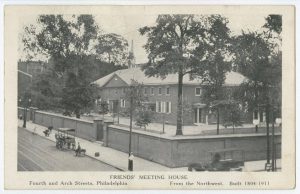

To exterior observers early nineteenth century Quakerism must take seemed to be a harmonious success story. A new meetinghouse was congenital on Arch Street in 1804, and the membership Quakers rolls were high. However just a few years subsequently Quakerism bankrupt into several rival branches.

Though each faction laid claim to beingness the "truthful" Quakers, many factors led to the split between what would be known as Orthodox and Hicksite factions. Among these issues, the Orthodox claimed that the followers of Elias Hicks (1748-1830), a popular Long Island Quaker preacher, overemphasized belief in the Inwards Light while underemphasizing the Bible. Hicks's followers accused the Orthodox of abandoning traditional Quaker teachings on these subjects. In 1827 this conflict reached the breaking bespeak during the gathering of PYM, when both factions tried to assert their rights to leadership.

The Hicksites stormed out the Curvation Street Meeting House and congenital their own meetinghouse on Race Street. Over the post-obit decades, Quaker yearly meetings in other regions of the United states of america experienced similar splits. The schism meant in that location were now two Philadelphia Yearly Meetings, ane Hicksite and ane Orthodox, with each side refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the other. By the 1830s, the Orthodox had established an all male person school exterior the city, which would eventually become Haverford Higher. Hicksites founded coeducational Swarthmore College in 1864, a few miles distant from Haverford. Decades subsequently, in 1885, the Orthodox helped established Bryn Mawr Higher to educate women.

By the 1840s, in other Yearly Meetings, the Orthodox faction had further divided into into separate groups, the evangelically-inclined Gurneyites and the more than traditional Wilburites. The Orthodox Philadelphia Yearly Coming together tried to avoid taking sides and substantially sealed themselves off from the residuum of Quakerism. The Hicksites also were in a land of upheaval due to intense arguments over how vigorously abolition and women's rights should exist pursued. A short-lived grouping, the Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting of Progressive Friends, even broke away from the Hicksite Yearly Meeting; for several decades they gathered at a meetinghouse in Longwood.

Reunification and Social Activism

Over the course of the nineteenth century Quakers in Philadelphia from both groups became receptive to liberal theological ideas, such as the thought that the Bible was the product of a detail ancient historical era, or the truth of the theory of the evolution. By the early on twentieth century Quakers had given up well-nigh of the peculiarities of dress and speech that separated them so visibly from the balance of the population, and began to intermarry with non-Quakers; they no longer saw these things as being essential to their religion. Religious leaders like Haverford Professor Rufus Jones (1863-1948) pioneered a new understanding of Quakerism as a mystical religion uniquely suited to the mod age.

Arch Street Meeting House was built on the city'southward primeval Quaker burial ground in 1804. Information technology was fabricated a National Historic Landmark in 2011. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

In the effort to reunite the divided parts of Quakerism, Jones and other influential Quakers helped to develop the American Friends Service Commission (AFSC), a Philadelphia-based arrangement intended to unite Quakers through a common involvement that would transcend the Hicksite-Orthodox theological separation by focusing instead on relief, peace, and charitable piece of work for others. The AFSC's efforts included advocating for interracial justice in the Usa, providing food to starving miners in labor disputes in Appalachia, and trying to rebuild Europe later on both earth wars. Ane of the largest undertakings was feeding millions of needy German children a day after the terminate of Earth War I. For its relief efforts worldwide, peculiarly during and after the world wars, the AFSC shared the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize with the English Quaker-run Friends Service Quango.

Quakers were a friendly presence during the Occupy Philadelphia demonstrations that were part of the nationwide Occupy Wall Street move of late 2011. Here, a Quaker-organized service takes place in the shadow of the City Hall encampment. (Photograph by Donald D. Groff for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia)

These shared efforts helped facilitate a reunification of the fractured PYM in 1955, which was function of a similar reunion undertaken by many of the other Quaker factions in the United States. Subsequent decades saw Philadelphia Friends trying to uphold their denomination's traditional testimonies of equality and peace by supporting the Civil Rights Movement. In the 1960s, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting tried to assist minority communities, undertaking community development project in Chester, Pennsylvania, and establishing the Minorities Economic Evolution Fund to fund like projects around Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Quakers also were harshly disquisitional of the Vietnam War. In 1967 Philadelphia Yearly Coming together expressed its back up for a grouping of Quaker activists who illegally sent medical supplies to Due north Vietnam in the send Phoenix, an action prompted by both humanitarianism and a desire to protest the ongoing conflict. Gay and lesbian issues were a 3rd area of concern; in 1973 PYM publicly voiced its support for gay rights, and by 1991 it was publishing a guide for same-sex couples that wanted to be married in Quaker ceremonies. Increasingly, the majority of Quakers in the Philadelphia region identified themselves every bit politically liberal, and many saw these beliefs as intertwined with their religious identities.

Quaker populations became substantially older in the twentieth century, causing many local meetings to focus on providing retirement care. By 2016 many Quaker-inspired retirement communities operated about Philadelphia, such as Kendal, Pennwood Village, and Foulkeways. Often they originated nonprofits at the prompting of members of local Meetings. These communities often boasted well-attended Quaker Meetings, though only a fraction of their residents were Quakers.

Since the mid-1970s Philadelphia Yearly Meeting has gathered at the Friends Center, a edifice at Fifteenth and Cherry Streets built in 1974. Statistics from 2010 indicated that the Yearly Coming together so had 11,800 members spread across the Philadelphia region amongst 106 monthly Meetings, a precipitous drop from more than than 30,000 members in 1775 or even the fifteen,000 recorded members in 1925. Although declining membership numbers have been a source of business concern for the denomination, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting'due south central part in Quaker history has meant that it continued to be an influential trunk within American—and indeed international– Quakerism.

Isaac Barnes May is a graduate of Harvard Divinity School and is pursuing a Ph.D. in Religious Studies at the University of Virginia. He has previously published manufactures in Quaker History and Quaker Studies.

Barbour, Hugh, and J. William Frost. The Quakers. Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Meeting Press, 1988.

Dandelion, Pink. An Introduction to Quakerism. New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 2007.

Dorsey, Bruce. Reforming Men and Women: Gender in the Antebellum City. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Endy, Melvin Jr. William Penn and Early Quakerism. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Fager, Chuck. Remaking Friends: How Progressive Friends Challenged Quakerism & Helped Save America. Durham, North.C.: Kimo Press, 2014.

Hamm, Thomas D. The Quakers in America. New York: Columbia University Printing, 2003.

Jones, Rufus Matthew with Amelia M. Gummere, and Isaac Sharpless. The Quakers in the American Colonies. London: Macmillan, 1911.

Larson, Rebecca. Daughters of Light: Quaker Women Preaching and Prophesying in the Colonies and Abroad, 1700-1775. Chapel Loma, N.C.: University of Northward Carolina Press, 2000.

Moore, John M., ed. Friends in the Delaware Valley. Haverford, Pa.: Friends Historical Assocation, 1981.

Russell, Elbert. The History of Quakerism. New York: Macmillian, 1942.

Affections, Stephen and Pink Dandelion , Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies. New York: Oxford Press, 2015.

Religion & Do: Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Yearly Coming together of Friends, 2002.

American Friends Service Commission Archives, 1501 Cherry-red Street, Philadelphia.

Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, Pa.

Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, 500 College Avenue, Swarthmore, Pa.

Peace Collection, Swarthmore College, 500 College Avenue, Swarthmore, Pa.

Curvation Street Meeting Business firm, 320 Arch Street, Philadelphia.

Friends Center, 1501 Cerise Street, Philadelphia.

Pendle Hill, 338 Plush Factory Road, Wallingford, Pa.

Stenton (the James Logan House), 4600 N. Sixteenth Street, Philadelphia.

Race Street Meeting Business firm, 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia.

Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Social club Historical Mark, 5th and Arch Streets, Philadelphia.

Source: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/religious-society-of-friends-quakers/

0 Response to "The Quaker Family in Colonial America: a Portrait of the Society of Friends by J. William Frost"

Post a Comment